The Math of Marketing: Interpreting ROI Numbers for Direct Marketing (Part 2 of 2)

In my last post I talked about the numbers you need to a) decide whether you should spend money on a particular marketing campaign and b) evaluate its results. Now let's investigate what the various numbers mean in terms of actions.

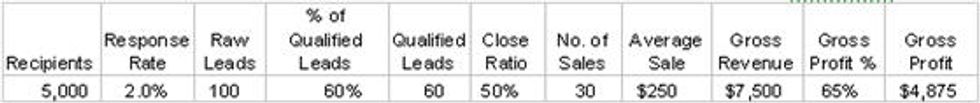

Here's a typical spreadsheet with the calculations for a marketing campaign:

If the response rate is low (under 1 percent), the problem is in one of the following:

- The list (not a high enough percentage of actual prospects)

- The offer itself (a product or a deal, such as 20 percent off, that simply isn't attractive enough to generate sales)

- The presentation (the copywriting or visual presentation; this is the least likely problem)

To help understand more precisely why results are good or poor, large scale direct marketers test different offers with the same list and different lists with the same offer. Unfortunately this isn’t always an option for smaller companies, but you should do it if you can.

If the percentage of qualified leads is too low (lower than half), the culprit is probably the list. The only way you can know if a lead is qualified is by asking, and that should be part of the sales process.

If the close ratio is low, the problem is either with what's for sale or how it's being sold. In other words, if a marketing campaign gets people to your Web site and they don't buy, the problem isn't with the campaign, it's with the Web site. Again, if your campaign gets an organization to ask for a quote and they don't buy, the problem is with the quote.

There's another type of direct marketing worth discussing that is unique to the Internet: search engine marketing. For most people, this will mean purchasing Google AdWords, the short text entries on the right side of the search results page in a Google search. The way it works is you actually bid on search terms such as “stainless-steel bolts.” Then when anybody types “stainless-steel bolts” in the search window, your ad pops up. And you only pay when somebody clicks your ad.

Actually, it's not quite that simple. Some search terms cost more than others. Some work better than others. You can spend literally hours every day analyzing and fine-tuning an AdWords campaign. The twists and turns of what you have to do to maximize your results could easily fill a book, and indeed there are plenty of books to give you advice.

My advice is simple. First, make use of the budget cap. You can set a dollar limit on how many clicks you want to pay for per month, and you should. Second, test one phrase at a time. Third, use the process outlined previously for analyzing results, but skip the first stage (number of recipients times response rate) and begin with raw leads.

No matter what your marketing activities may be, it’s a good idea to remember the rule used by engineers: You can’t improve what you can’t measure.